This article was originally posted on Bloomberg by Dani Burger with assistance by Miles Weiss. Click here to read the original article.

Wall Street’s quant wizards often argue that many of their math-driven strategies are designed for the long-term. But they’ve rarely had to shout this loud.

Global equities posted the worst run in six years in “Red October,” and it tore through the investing styles that slice and dice assets based on traits like momentum and growth. Most factor funds, as they are known, fell in concert with stocks. That not only capped an already miserable year, it threw into doubt their diversification benefits — forcing advocates onto the defensive.

Cue Cliff Asness, godfather of quant investing and co-founder of the firm which helped popularize factors, AQR Capital Management. In a 23-page, 17,000-word blog post in October he acknowledged the strategies AQR favors have had “tough times,” predicted no miracle bounce back, but argued the evidence and common sense dictate they will ultimately prevail.

“I admit I’m nervous. Not about the efficacy of our strategies,” Asness wrote. “But I admit I’m nervous about how our clients will react (this is correlated with my writing this fairly giant essay). Will they truly stick with what we’ve started together for the long term?”

The lengthy apologia and Asness’ concerns speak to how the recent performance of factor strategies is becoming a huge test of the quantitative-investing boom. Evidence is growing that assets are under pressure, and critics claim that unwinding from funds under duress helped lash equity markets last month, compounding the declines.

Factor funds haven’t been “diversifying to the market when you’ve needed it this month,” Maneesh Shanbhag, who co-founded Greenline Partners LLC after five years at Bridgewater Associates LP, said. “They get correlated repeatedly over time, and marketing pitches of these funds have largely ignored that.”

Value Hit

For AQR, which oversees $226 billion, the challenge has been particularly acute.

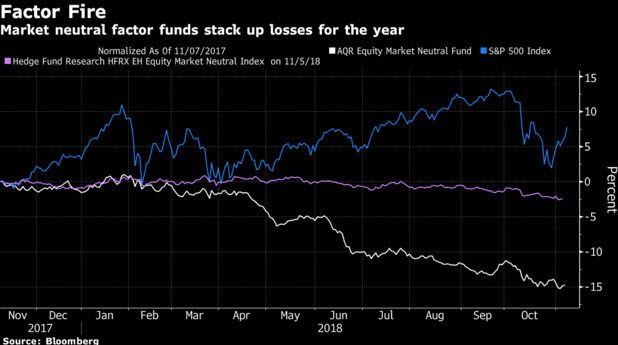

The firm’s equity market neutral mutual fund declined 4.7 percent in the three months through Tuesday, versus an average drop of 1.4 percent for all equity market neutral hedge funds, according to Hedge Fund Research. While that was only a little worse than the S&P 500’s 3.6 percent slide in the period, it took AQR’s full-year losses to 13 percent compared with a 5.3 percent gain for the main U.S. stock gauge.

Market neutral funds aim to eliminate broader market risks through hedging. It’s a key part of the AQR proposition, which is to offer liquid strategies that have low correlations to traditional assets. Asness and his colleagues argue recent moves haven’t negated their funds’ diversification benefits — they’re uncorrelated over the long haul, not hedges for day-to-day losses.

“We have seen relatively normal factor volatility, factor correlations and transaction costs,” said Ronen Israel, a principal at AQR. “There’s no evidence that the underlying themes are behaving in a way that is symptomatic of factor deleveraging.”

Rather, AQR’s bread-and-butter funds were hit by a temporary yet especially sharp sell-off in value — a factor favoring cheaper stocks, and a favorite among the managers. Though value staged a slight rebound in late-October, other factors like momentum declined. Making matters worse for AQR, value as measured by a simple price-to-book ratio staged a stronger return than the composite measure used by the firm.

All of which makes it hard for investors to keep the faith, as even Asness acknowledges in his post. But as he points out, that’s exactly why the strategies work in the first place.

“If sticking with them were easy, the threat of them being ‘arbitraged away’ would indeed be much greater, and nobody would take the other side,” he wrote.

Money Moves

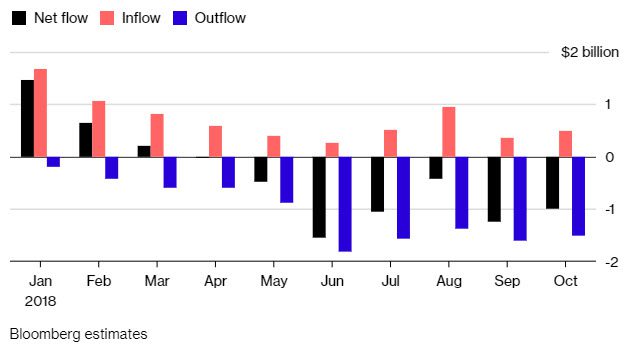

All the same, there’s emerging evidence of retail money leaving AQR. UBS’s Pace Alternative Strategies Investments — where about 7 percent was invested in two AQR funds — terminated the Greenwich, Connecticut firm as a subadvisor due to “an asset reallocation determination” on Oct. 19, according to a filing. In September, AQR mutual funds saw $1.1 billion in outflows, the fourth biggest outflows of any U.S. fund family, according to Morningstar data.

“Could the recent factor performance be partly driven by investors changing their hearts and pulling their money from corresponding funds? Perhaps,” Vitali Kalesnik, head of equity research at Research Affiliates LLC, said. “Factor performance is generally mean-reverting and fund flows likely play a big role in it.”

In AQR UCITS and mutual funds, investors this year pulled a net total of $3.5 billion through October, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. A managed futures fund, which chases momentum across assets, accounted for $2.2 billion of those losses alone.

Fleeing Funds

AQR mutual funds and UCITS turn to net outflows in April.

But the outflows stop short of institutional clients, where there have been net inflows this year, according to the firm.

“For the most part, our clients understand the economic intuition behind our strategies and appreciate the long-term supporting evidence,” said David Kabiller, co-founder at AQR. “Good strategies can go through tough times.”

‘Hold Your Nose’

Peter Sleep is standing pat with AQR, even while some of his colleagues at Seven Investment Management LLP in London have sold out. The senior portfolio manager owns trend-following and style premia funds from the quantitative manager.

“AQR gathered a lot of assets with people putting money on trends, and trends haven’t worked out,” Sleep said. “But you have to do your homework, hold your nose, and place bets in the long term that you’ll get an equity risk premia.”

And for some, exiting is just a temporary tactic, and says nothing about confidence in the quantitative giants. At the start of the year, Sierra Investment Management held one of the largest position in the AQR Equity Market Neutral mutual fund, worth about $22 million, according to filings. Because Sierra jumps in and out of factors based whether they’re predicted to outperform, it sold out mid-year as the mutual fund moved into a “confirmed downtrend,” according to Terri Spath, chief investment officer at the California money manager.

“Factor tilts aren’t reliable over a shorter time frame,” Spath said. “We use our own rules to decide when to play in the sandbox with the quants and the rules that dictate their play.”

And the funds are hardly alone in suffering through October. ETFs also struggled, with the Goldman Sachs ActiveBeta U.S. Large Cap Equity and iShare MSCI U.S. Multi-factor ETFs each dropping more than 7 percent, both funds’ worst month since launching in 2015. Pure momentum and pure value funds from Alpha Architect fell more than 16 percent and 7.5 percent, respectively, compared with an S&P 500 decline of 6.9 percent.

Diversification Fail

Meanwhile, it’s difficult to say whether selling from factor funds had a big impact on wider markets, but something certainly is amiss.

Drivers like the dollar and yield curve have lost their explanatory potency — equity returns are now best explained by factor exposures, Evercore ISI’s risk models show. Macro risks only accounted for 26 percent of the S&P 500 Index’s returns at October’s end, falling from 41 percent over the span of three weeks, according to the firm.

“It is not the macro backdrop driving factor volatility, but likely something more specific to quant positioning,” said Dennis DeBusschere, Evercore’s head of portfolio strategy.

Research backs up the idea that investor redemptions create systematic bursts and strange correlations. But that means perceived diversification benefits fail when most needed, according to Rama Cont, a University of Oxford professor whose paper, first published in 2012, examines the phenomenon.

“It’s exactly the same thing that happened in the quant crash in 2007,” Cont said. “Investors are not passive — their typical reaction is to deleverage in a big loss. That reaction has to be included into models, otherwise you don’t see the concentration risk.”